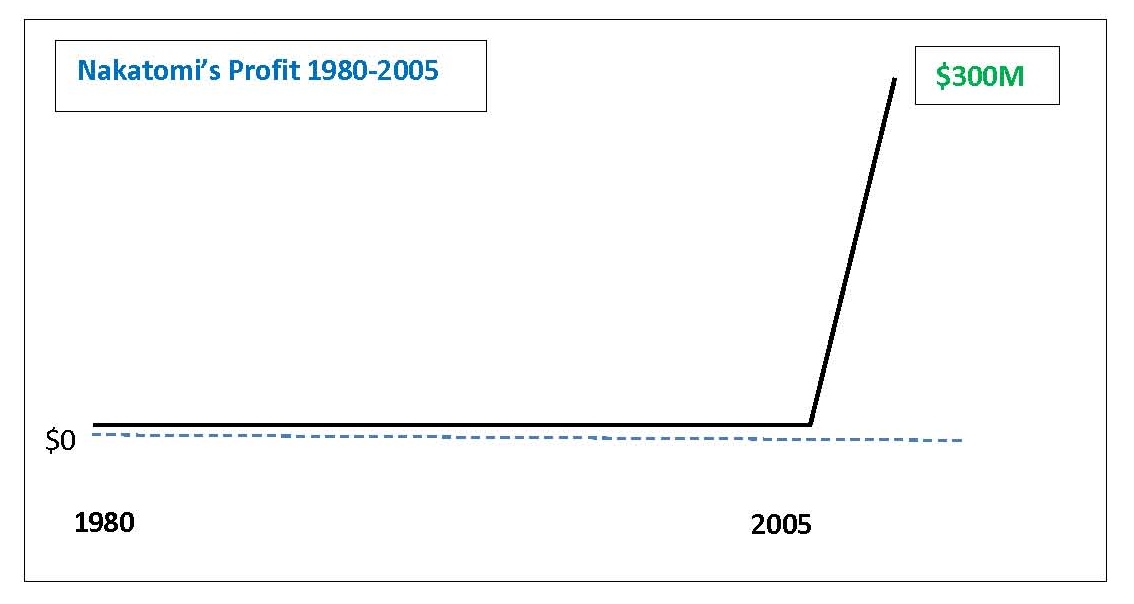

You’re an executive leader in Nakatomi and you see this chart, what do you do?

You’re an executive leader in Nakatomi and you see this chart, what do you do?

- Shout like Homer Simpson “Wooohooo!” and deposit your bonus check.

- Go to your daughter’s swim meet—the whole time thinking ‘we need to understand why this happened.’

- Convene a company-wide meeting, congratulate everyone on achieving the extraordinary, and hand out bonus checks.

- None of the above.

Maybe there should be an option for ‘all of the above.’ Have you been a part of an organization that achieved this type of sudden and meteoric success? I have not. Still, it’s compelling to imagine the ways that such success influences thinking among leaders and contributors alike.

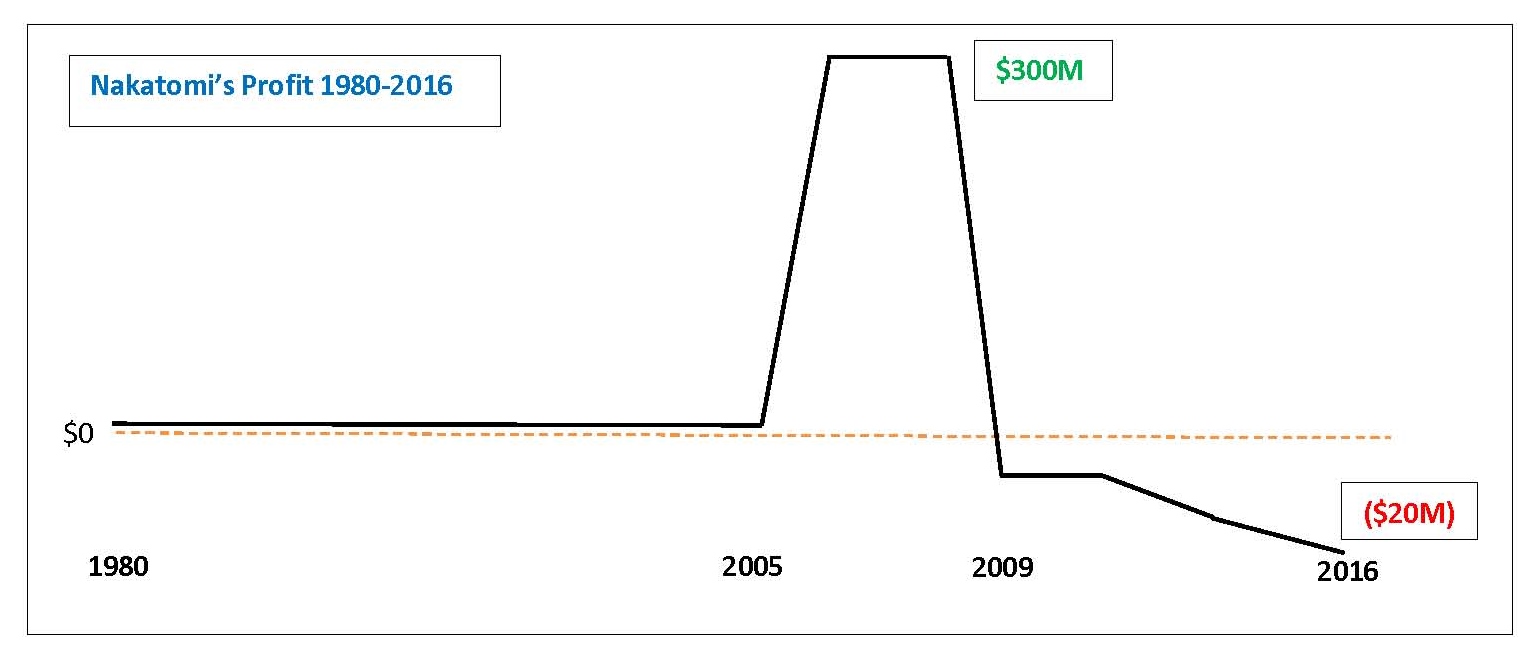

As iconic radio personality Paul Harvey would say, ‘And now…the rest of the story.’ Or a snapshot of it, anyway.

This post was co-written with Holly Gennero (not her real name), Chief Human Resources Officer for Nakatomi (not the company’s real name). Nakatomi is a private consumer products company. Holly has a seat at the C-suite table during the past nine years. She is still in her leadership role and, understandably, wants to remain anonymous. However, she expressed a strong interest to convey her lessons learned with the intent that other leaders may learn without going through a similar arc. In 2012 Next Level was invited into the organization to help the executive team align and collaborate more effectively.

Historical Context

From 1985 to 2005 Nakatomi’s profits were hovering around breakeven. From 2005-2007, with the robust economy and some highly favorable tail winds in Nakatomi’s market, the company’s products were in high demand. Consequently, profits skyrocketed to $300 million per year. In 2009 the impact of the financial crisis hit the company hard. Unfortunately, around the same time, a couple of internal missteps combined with the financial crisis sent profits falling as fast as they rose. In 2010 the organization lost $10 million. In 2016, the loss was close to $20 million. Many companies were hit hard with the financial crisis of ’08. Some recovered, others did not.

Here are 3 questions Holly and I asked each other with the intent of drawing out possible learnings for others.

- Was there an event—or a series of events—early on that the executive team should have heeded while there was still time to act?

Holly: If there was one event that acted as a canary in the coalmine—one that in retrospect I wish we on the executive team had paid much more attention to—it was our unprecedented success in 2005-06. When profits skyrocketed in 2005 none of the executives identified that this was chiefly the result of a windfall in market prices and having no national competition. Instead, we flew around the country giving self-congratulatory presentations on our ‘best practices.’ As executives we should have seen this enormous jump in profits for what it was—right place and time—and invested those profits in systems that would bolster us from the next downturn. The canary in the coalmine? Ironically, it was our abrupt and extraordinary success that should have triggered us to ask much deeper questions.

Tom: For me, it was when the largest customer stopped doing business with Nakatomi due to one of those missteps. I remember being part of an executive team discussion when the CEO suggested to the VP of Sales that they visit that #1 customer together with a plan to win back the business. The VP of Sales resisted, explaining that this would look desperate. The CEO acquiesced. I suspected that there was something else going on there: the VP of Sales didn’t want the CEO looking at new—potentially business-saving—pricing strategies; and the CEO didn’t want to appear as though he was looking over the shoulder of a friend and direct report. The key customer—and the high volume sales—never returned. The dynamic between the VP of Sales and the CEO was just as accurate an omen as the departure of the largest customer.

- If we experience a similar situation in the future, what would either of us do differently?

Holly: This is a tough one for me. By the time 2013 arrived we were already 3 years in the red and dealing with an almost entirely new management team. I was the person ringing the alarm bell. My sense is that they saw me as an outsider or possibly part of the problem and did not include me as closely in the strategy sessions that would determine the path forward. In hindsight I could have fought harder to be a part of those conversations because I knew without massive change—in both the ways we were doing business internally and externally—the business would ultimately fail. It was as if the business was tied to railroad tracks and all I could do (or maybe did) was hear the train get closer and closer.

Tom: Look, here is the stark truth: I failed to convey the right level of alarm to the CEO and the exec team in 2012. I was engaged with the expectation to coach the CEO on his inclusiveness and subsequently to help the executive team align. I was not hired as a turn-around consultant. At one particular exec team meeting I facilitated, I took a risk and stepped outside of my defined scope of work: I asked the group about the organization’s burn rate and how long they would tolerate mounting losses before committing to a different path of action. In retrospect, I should have pressed the group harder to identify alternative income-generating solutions other than just cost cutting and RIFs. In the future, I would facilitate a data-based dialogue that would start with: “Let’s review and reality-test all the actions you are currently taking to increase income.”

- How can an executive team—in any market—act on the most critical priorities when, often, those priorities are the most uncomfortable to implement?

Holly: It’s trite to say it, but the attitude of the organization is set from the top. If the senior executives aren’t doing things that stretch themselves and are uncomfortable, why would any of the employees do likewise? Yes, it would have been difficult and uncomfortable as hell for the executives to develop and stick to a radical business-saving plan. It would have been equally uncomfortable for us as executives to hold town hall meetings with employees, customers and vendors to address rumors and defend the credibility of a path forward. We didn’t do this and maybe as importantly, we didn’t have anyone on the executive team who suggested and championed taking this type of bold approach. I guess to answer the question, I’ll pose another question to whomever is reading this post, “Does your leadership team regularly demonstrate the norm of peers challenging each other and the boss to do things that are uncomfortable?”

Tom: When it came to doing things that were uncomfortable, one of the most perplexing things happened during an executive team meeting in 2016. It was the end of a two-day SWOT business analysis. The group had identified a handful of powerful and actionable next steps that—if implemented—increased the likelihood of righting the ship. When the group multi-voted with their sticky-dots, the top vote receiving action was…wait for it…leadership development for mid-level managers. I was stunned. Nakatomi was bleeding 5 years in the red and the executive team comprised of smart, capable people prioritized leadership development as the most important and urgent thing to do. I remember saying to the group, ‘I can’t believe I—as the leadership development guy—am about to say this, but are you absolutely sure leadership development is the first next step to get the business back to profitability? There is a hole in the boat. We need to plug the hole first; then we can do the important work of developing your leaders.’

The room went quiet and everyone looked to the CEO who declared, ‘I think we’ll move forward with leadership development. That is what is going to make the difference.’ I didn’t agree with the exec team’s decision, but I understood how they arrived at it: it was the easiest action to implement. If faced with a similar situation in the future, I will ask the executive team to demonstrate the causal relationship between doing x and getting y. “Help me understand how developing mid-level managers will stop the $20 million year-over-year loss.”

Closing

Holly and I understand that the organizational development landscape is overflowing with literature on companies that didn’t heed the warning signs or didn’t act quickly enough. In the best and worst of times we encourage executives to remain intently curious and ask consequential questions. Among them, “How are we getting the results we’re getting?” and “How do we create an environment among executives that values tough questioning?”

Hopefully, hearing from someone who, like Holly, sits at the executive team table provides valuable perspective. Our first concern is with the current leaders and employees as they continue to look for ways to strengthen the balance sheet and overall health of the organization. A close second wish is for all senior leaders to gain insight from Nakatomi’s arc so that they might avoid—or minimize—a similar experience.

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment